A Normal Person Theory

- Dedicated to all fellow problematic participants.

Introduction

For those who know me, this doesn’t come as a surprise: I consider myself - what most people would call - a normal person. I have a semi-steady precarious work. I like YouTube. Fried food. Driving cars. Shiny things. Sex. I spend most of my days on the computer. I like and dislike people. I went through both of the stages of loving people and then hating them. Now I like them the normal amount.

The unusual thing about me is that I live in a village with 22 inhabitants. If I want to eat some potato chips, I have to jump in a car and drive 15 minutes to the first shop. If I want to go to the cinema - 45 minutes. To the doctors or the library - 1 hour.

I wasn’t always living here. I sometimes still think of the times I lived in Ljubljana. During the last year of my studies, I lived in the ugliest and oldest of houses in a beautiful and rich neighborhood, just 5 minutes from the store. But I remember that putting on my clothes, shoes, peeing before leaving - just in case - and dealing with the stairs of the house took me about the same 15 minutes as it does here. Going through the dirty grey snow made me hate winters.

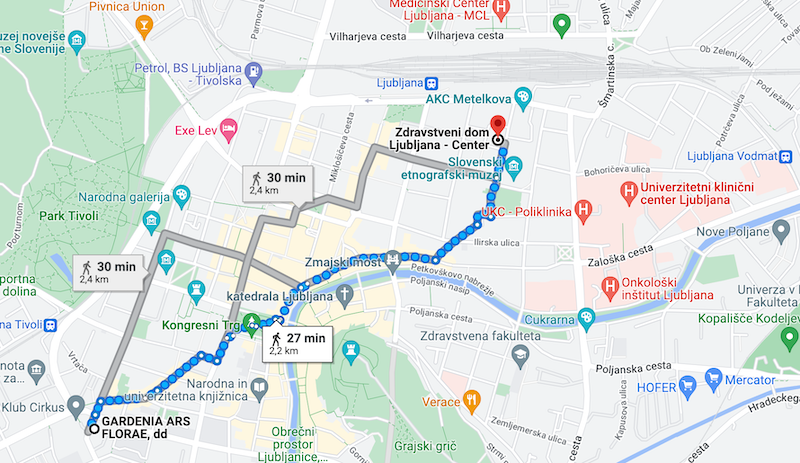

When I had my first heart condition, I walked to the doctor. Ljubljana is filled with medical centers, full of doctors. One of those was around 500 meters away. But I called the one that was around 2,5 km away. I don't know why I did that. And then it just seemed more simple to not call a different doctor and just go to the one on the other side of the city. This is the route I did through the snow:

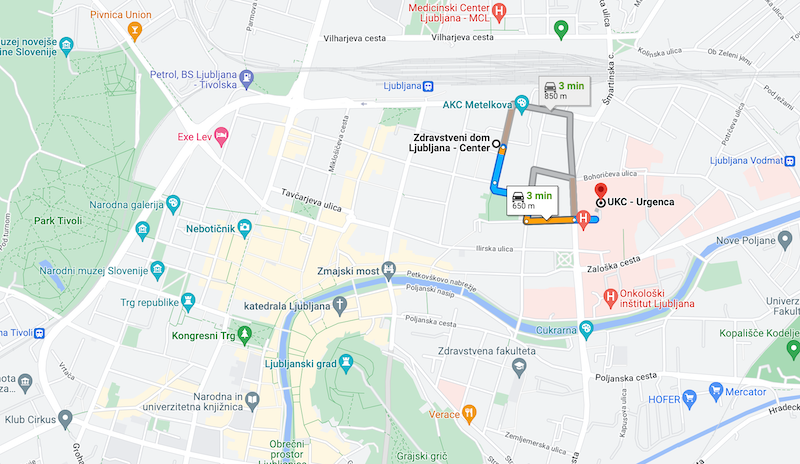

When they told me I had a condition called myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) they drove me in an ambulance car to the University Medical Center. They said I shouldn't do another step by myself, it can be bad for my heart. They put me in a wheelchair and we drove off. This is the route we did:

There I waited in a wheelchair for about 4 hours.

What I want to say is, that going to the doctor always takes a lot of time. Plus, minus 1 hour - it doesn't really make a difference.

Going to the cinema is now a real event. Putting on my good clothes, polishing the Dr. Martens shoes. After the film, we always go for a pizza. I like it this way, it makes it a special day - a cinema day.

Convincing people that you’re a normal person is not always easy. I thought that writing a book about it, explaining my positioning in the world, for all the interested people to read, would make it easier. But it turns out it doesn’t. Can you remember the last time a normal person wrote a book on the psyché of a normal person? Normal people don’t want to write books with titles such as: (1) On Stuttering Literature and Philosophy: How to Stutter Your Way Through It?, (2) Noli me tangere: How to Fuck the Police and Get Away With it? or (3) A Long History of Decay: Why Do We Hate Putrefaction? But I do think that a book on the normal person is one of the most important books to write, even if it makes the writer be perceived as less of a normal person. That’s the risk philosophers just have to take.

The topic has ethical and political significance and it at the same time also deals with strategy. Philosophers are terrible strategists. Stratēgós in Ancient Greece was the leader or commander of an army; a general. To have a strategy means to be a general. Of the general and the generic. Philosophers who have the most to teach us on the question “how to live?” were all loners, lone wolfs. Exceptional people, in their own ways. The philosophers of life: Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky, Heidegger. They turned existence into the most fundamental question a human being can pose. But they were all exceptional. And how can an exceptional man pose a question on existence, on the category of being which is spread so democratically among all of the people - most of them ordinary?

Nietzsche went mad after seeing a horse getting beaten one day in Torino. He was more of a philosophical hero - and a great drama queen - than a general. On the common people he wrote: “All very individual rules of life excite hostility against him who adopts them; other people feel humiliated by the exceptional treatment he accords himself, as though they were being treated as merely commonplace creatures.” (Nietzsche: Human, All Too Human, 1986: 180) But it was he who made a hateful dragon out of a normal person, following his theory of heroism: “If a man wants to become a hero the serpent must first have become a dragon: otherwise he will lack his proper enemy.” (Ibid.) In reality, a normal person does not care about the hero. Philosopher’s phantasms about him being disliked because he is extraordinary are just that - mere phantasms. A normal person does not care about him, because he finds him not-relatable.

Kierkegaard was not normal. He never worked for a living: 31,000 rigsdale of his family’s inheritance was enough to be a professional sufferer. The only job he knew was Job, the patron of the depressed. And although he expressed admiration for the common man (“You common man! I have not segregated my life from yours ... So if I belong to anyone, I must belong to you.”), his truly important concept was the one of the crowd: “By seeing the multitude of people around it, by being busied with all sorts of worldly affairs, by being wise to the ways of the world, such a person forgets herself, in a divine sense, forgets her own name, dares not believe in herself, finds being herself too risky, finds it much easier and safer to be like the others, to become a copy, a number, along with the crowd.” But he does not propose an antidote of a general with deep resonation with the crowd; no, he proposes a single individual, similar to a hero, but this time with “a spindly figure, a humped back, tousled head of hair [which] made him look like a scarecrow”. Scaring the normal people away.

And Dostoevsky was a gambling-prisoner-put-on-death-row-heavy-drinker kind of guy. Nowhere near generic. He was the architect of Raskolnikov from the novel Crime and Punishment (1866) who speaks of the ordinary man:

As for my division of people into ordinary and extraordinary, I acknowledge that it’s somewhat arbitrary, but I don’t insist upon exact numbers. I only believe in my leading idea that men are in general divided by a law of nature into two categories, inferior (ordinary), that is, so to say, material that serves only to reproduce its kind, and men who have the gift or the talent to utter a new word. There are, of course, innumerable sub- divisions, but the distinguishing features of both categories are fairly well marked. The first category, generally speaking, are men conservative in temperament and law-abiding; they live under control and love to be controlled. To my thinking it is their duty to be controlled, because that’s their vocation, and there is nothing humiliating in it for them. The second category all transgress the law; they are destroyers or disposed to destruction according to their capacities. The crimes of these men are of course relative and varied; for the most part they seek in very varied ways the destruction of the present for the sake of the better. But if such a one is forced for the sake of his idea to step over a corpse or wade through blood, he can, I maintain, find within himself, in his conscience, a sanction for wading through blood—that depends on the idea and its dimensions, note that. It’s only in that sense I speak of their right to crime in my article (you remember it began with the legal question). There’s no need for such anxiety, however; the masses will scarcely ever admit this right, they punish them or hang them (more or less), and in doing so fulfil quite justly their conservative vocation. But the same masses set these criminals on a pedestal in the next generation and worship them (more or less). The first category is always the man of the present, the second the man of the future. The first preserve the world and people it, the second move the world and lead it to its goal. Each class has an equal right to exist. In fact, all have equal rights with me—and vive la guerre éternelle—till the New Jerusalem, of course!

What happens with ordinary people in the New Jerusalem?

Dostoevsky was saddened because of the fact that for normal people he and the intelligentsia who tried to break the chains of oppression of the lower classes were viewed in the same kind of way as the ruling class which provided and locked the chain. Anything out of the normal - above or bellow it - is considered oppressing.

A general and a strategist have to be in an intimate resonation with the generic. One simply cannot speak of politics while disregarding most of the people and putting them into the category of the They. Martin Heidegger, the influential German philosopher, used this clever term of the They - das Man in its original German version - in his magnum opus Being and Time (1927):

In utilizing public means of transport and in making use of information services such as the newspaper, every Other is like the next. This Being-with-one-another dissolves one's own Dasein completely into the kind of Being of 'the Others', in such a way, indeed, that the Others, as distinguishable and explicit, vanish more and more. In this inconspicuousness and unascertainability, the real dictatorship of the "they" is unfolded. We take pleasure and enjoy ourselves as they [man] take pleasure; we read, see, and judge about literature and art as they see and judge; likewise we shrink back from the 'great mass' as they shrink back; we find 'shocking' what they find shocking. The "they", which is nothing definite, and which all are, though not as the sum, prescribes the kind of Being of everydayness.

Is this a way of speaking to a normal person? Is bringing Heidegger’s Dasein to extra-ordinary authenticity the smartest way of making it do what it should do, what the They should do? A normal person does things as one does them. In its everydayness, a typical normal person will never be authentic. Impossible. Stating otherwise is a clear case of intellectual dishonesty. An authentic normal person is a contradictio in terminis. But the question remains: Can we think of ways of showing that a higher quality of life can be achieved also by staying true to ourselves, to the They in us?

How can a radical position be presented as a normal one? These writings will therefore also speak of a more specific question I was - and still am - sporadically thinking about in the past couple of years, the question of city-quitting.

What Is a Normal Person?

There are of course numerous typologies of a normal person, as Raskolnikov mentioned before. Most of them don’t take strong positions and don’t have strong opinions. But contrary to the belief, they do have opinions. I can already smell the critical philosopher getting closer, his breath stinks of criticism: ‘’The normal person is responsible for the rise of the radical right-wing politics of the last decade! Down with the normal person!’’

Not true. Some of the normal people don’t vote. Normal people don’t believe in voting. Normal people don’t love or hate and those two are exactly what makes you go and vote. But if they do go and vote, as the educated normal people usually do, they do it because deep down they know that voting will not change the game. And I don’t think that they think this in a cynical kind of way. They just know it. And they are fine with it. Normal people are OK with what they have. Actually: they feel great with what they have! They are not stoics. They feel good with what they have, regardless of what they have, and especially because of what they have. A normal person likes to feel comfortable. Sometimes they’ll deny the upper diagnosis, but that’s also what normal people do.

If a normal person is born in a city he will most probably also die in the city. ‘’No reason to move. The city is a comfortable place.’’ They don’t say that, but they know that. I respect that.

In a philosophical tractatus, now would be the perfect time to initiate the critique: ‘’Being comfortable is not what people should strive for! People should strive for greatness and love between all that is! Sing with me: Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité!’’ I also respect that. A normal person is inclusive when it comes to ideas, he understands all of the positions. He is happy for there being extra-ordinary people with strong opinions, doing extra-ordinary things. Again, he is not a cynic. But he will simply not follow. Extra-ordinarity is either (1) something others do or (2) something to only think about. Dream about. Extra-ordinarity is a dream-like place where you at the same time wish to go and not wish to go to. It’s like going to the spa. You like the hot thermal water, but you just hate the screaming children.

Keeping with the spatial analogies: There is this dream-like place in the mind of a normal person. And then there is the real life. Real life is the quintessential space of the normal person. It’s the space they always return to. It’s there. And in reality, real life may seem tough and hard, but normal people find it soothing. It is the stuff out of which the void between people is made of.

Are you a normal person? To give a simple ‘yes’ would be to underestimate yourself. Because there is also a ‘no’ to this question which resides in a normal person. Normal people are a complex system of simultaneous yay-and-nay saying. With some the ‘yes’ prevails, with others, the ‘no’, but both are there at the same time. Don’t downplay yourself by saying ‘no’. We all know that the most normal of the persons denies being a normal person. That is a tactic normal people use to not fall into the mass of the they. And don’t simply say ‘yes’. We know you are just trying to hide the ‘no’ behind the ‘yes’. Because remember, there is a dream-like space in each normal person.

Everyone is a normal person. Some are just a bit more crypto than others. It’s the same with sexuality. When I was at a summer school of Danish language a couple of years ago, I had a Polish flatmate who thought a lot about sexuality. He told me that at least 50% of Polish men are cryptohomosexuals, stating it as a firm fact. As he was obviously also one of them, I figured that the meaning of the word crypto is not only in not being sincere about one’s own sexual preference to the outside of the others but also to the inside of the self. Some of the cryptohomosexuals were homosexual and they didn’t even know about it. It’s the same with normal people.

But the one thing I want to avoid is making a superman out of a self-proclaimed normal person. He cannot change the world - he can only change himself. Are there is another reason why a normal person is not superman-like. There is nothing hidden behind the surface of the normal person. To use one of Slavoj Žižek’s overused jokes: This person may seem like a normal person, he may talk like a normal person, eat, drink, shit, write, love, and think like a normal person. But don’t let that fool you: He is a normal person.

But a normal person can, despite all of this, still do the right thing. Strategies are needed to make him do that.

Normal Person Strategies

It’s not that philosophers haven’t written about the normal and the ordinary. You can actually leave aside the high-brow philosophers who spoke about the ordinary for the simple reason of distancing themselves from it; the ones who spoke of dirt only to reach the heavens. Or the ones who touched upon the petty individual only to dump it later and dip their feet into the sea of universality. These thinkers - the classic metaphysicians and theologians - go by the simple rule of thinking of the ordinary for one reason only: to reach the extraordinary. Makes sense: If you know and recognise the smell of shit, it’s easier not to step in it. And if you know the smell of shit, the non-shitty things smell even better.

But there is another category of thinkers, the mystics and poetical metaphysicians, the Poets. They do a clever poetical turn in the upper mentioned logical operation. After smelling shit long enough, they start to like it, they start sensing the sweetness inherent to it. These extra-ordinary individuals see and smell and taste what others usually don’t. They find sweetness in shit, love in death, universality in the individual. They turn the invisible into visible, they see rocks move, and they grant them agency. Can you imagine a rock moving on its own? Well, they do. They give stuff value, while the classic theologian gives value to Values. I like both of these hermeneutical strategies, I also use both. On the one hand the Pure Spirit, on the other, stuff as ‘’avatar of Spirit’’ as Michael Marder said summarising G. W. F. Hegel. Sometimes it’s nice to think of the important stuff and forget about the unimportant details. Sometimes unimportant details are just that - unimportant. But sometimes looking at the sky - oh, the starry heavens above me! - makes you fall into a well and you become a laughing stock of old women. And still, I use both of these strategies. I believe that thinking about pure, a priori happiness is the only way to witness true happiness: not people, not relationships. Only conceptual, restricted, a priori ways can bring us to the Truth. On the other hand, a small footprint of a cat in the snow is truly touching, it makes me see that we leave footprints everywhere, our traces are omnipresent. Everything leaves a trace, even the smallest worm buried in the forest that no one actually saw before does. That’s truly touching.

But, there is another strategy - the one of the normal person. The first philosopher speaks of the extra-ordinary without the ordinary, the second of the extra-ordinary in the ordinary. The normal person’s strategy is on the other hand in speaking of the ordinary in the extra-ordinary. The first philosopher counts on Truth, the second on Beauty (which for him equals Truth). Truth, Beauty - these ‘’are nouns for young people, for outsiders, clerics, sociologists,’’ as Peter Sloterdijk nicely put it. The normal person speaks not of Truth or Beauty. He wants to be effective. If he wants to be anything at all. This brings me to the already mentioned fact that philosophers are terrible strategists. Can Truth be truly effective? When was the last time a normal person did something because it’s true? (Take in account that it’s not 1968 anymore.) Normal people don’t do stuff because it’s true. They do it because they either want to do it or are simply used doing it. This is how a normal person acts. Extra-ordinary philosophers will disagree, but it takes a normal person to know a normal person. Maybe normal people don’t actually think like that, as most of the time a well-meant normal person actually believes he is in pursuit of Truth. But he is not. There is a radical discrepancy between thinking and doing, as we all know. Yet extra-ordinary people still insist in believing that good thoughts lead to good acts. They insist on the idea that the smarter the man, the better the act. If I know that there are millions of bacteria making it possible for me to move my elbow, this should somehow make me appreciate these bacteria. It doesn’t. No matter how many words you write about it, no matter how many poems, I’ll never truly appreciate bacteria. Don’t get me wrong: I don’t hate bacteria. But I’ll always be neutral about bacteria.

Neutrality is the ethos of a normal person.

Most philosophers thought that this is not true. Just take Aristotle for example: In all he does, man seeks Good! All men by nature desire to know! Why does he have to write so radically about normal people? Why do philosophers always fall in these extreme positions? A normal person sometimes seeks good and sometimes doesn’t. Sometimes he seeks evil. But most of the time he just seek neutrality. It’s true that sometimes a normal person desires to know. But sometimes he desires to stay as far away as possible from knowledge, as sometimes knowledge hurts. But most of the time, a normal person thinks he knows enough. He doesn’t want to know more and he doesn’t want to know less. What he knows is what he knows - and that’s enough.

One of the tasks of convincing a normal person of doing something is to make this thing seem neutral and normal. Extra-ordinary decisions don’t have to destroy the fundaments of your way of living. A normal person doesn’t really want to change the way he lives. Or he at least doesn’t want the change to be a true change, a total game-changer. This, again, sounds like a moral statement. But it’s not. Can you blame a normal person for wanting the new to fit with the old? And to accumulate and not discard at the same time?

But wrapping your desire to make a normal person do something is not enough. Normal people do not trust easily. They know that you are trying to sell them extra-ordinary stuff in the guise of normality. Remember: they are not stupid. So, you need to actually be a normal person to convince another normal person. Luckily, there is a normal person inside of you. Try to be that part of you for a change.

But where to look?

I would like to point out four normal person strategies.

The first one is the most obvious one: be a normal person.

In the above-mentioned case of city-quitting, this strategy goes something like this: A normal person has a hard time relating to hippies, DIY-anarchists, or even semi-hippies/modern-agriculturists. He knows that he cannot be a part of those three groups. He appreciates them, yes. But he cannot be in one of them.

Hippies saying All Is One and that only the present matters are a typical miss for a normal person, as he knows that all is not one, but many, and that not only present matters, but also the past and the future do. DIY-anarchist are just too smelly and angry looking. They feed on non-normality, they are proud of it. Semi-hippies/modern-agriculturists are doing the right things! But a normal person does not want to spend all his time in the garden or create himself a job out of gardening. He likes to garden, but he prefers doing that in his spare time, just for fun, an hour a day maybe. He prefers doing other things: reading, drawing, eating good food, and having a meaningless job. Meaningless jobs are sometimes good, especially if they don’t take all of your time. They make you appreciate the spare-time you have. A normal person likes the forest, but doesn’t love it.