Robida thorugh 4 words: MEJA, KOZOLEC, VAS, POSTAJANJA

This series of texts was commissioned by and published on AFIELD IG profile as a digital residency.

The invitation was to reflect and share inspirations, genealogies, key concepts of Robida. We tried to do it thorugh 4 words: meja (border), kozolec (hayrack), vas (village) and postajanja (becomings).

MEJA (sl. border)

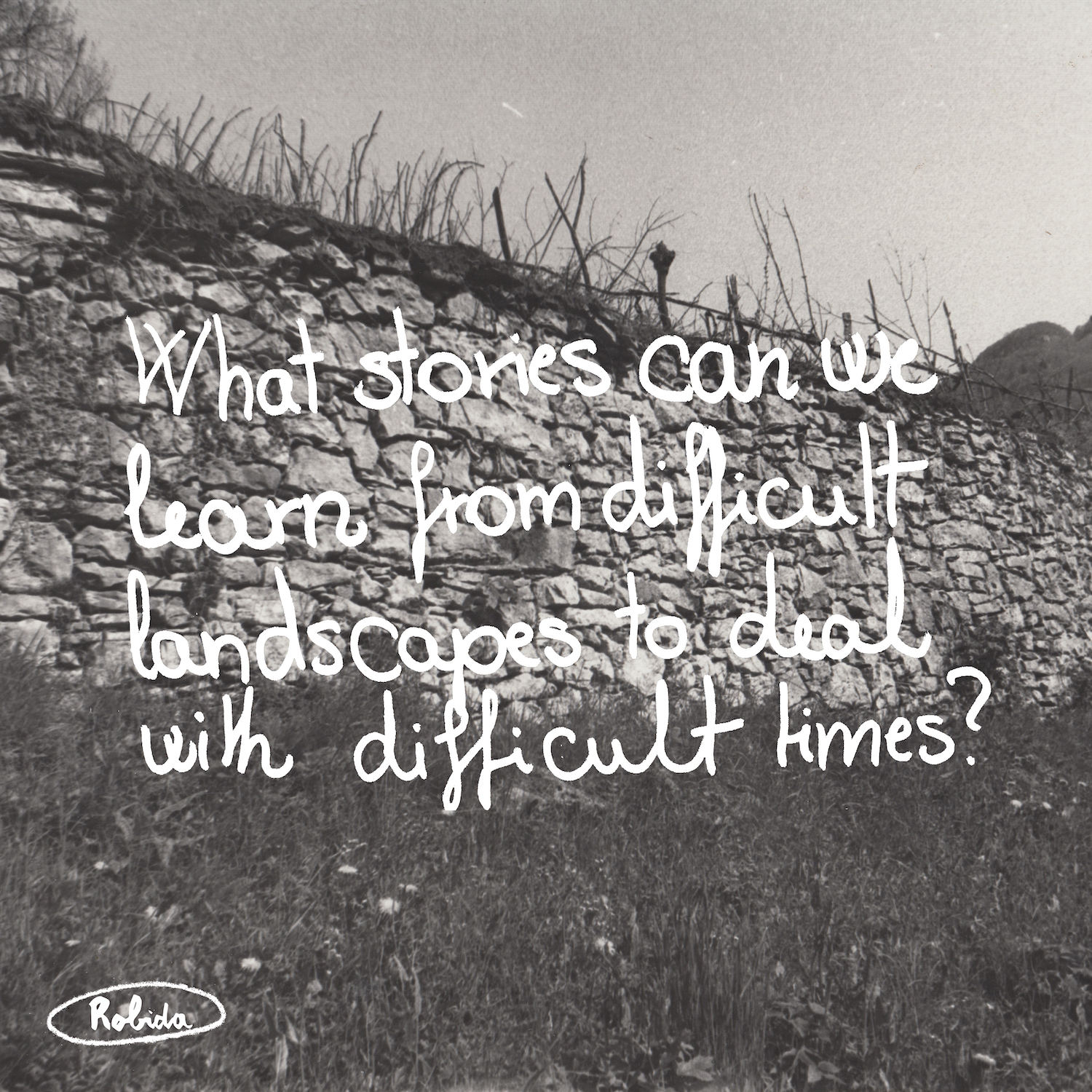

Meja is the Slovene word for ‘border’. In contrast to Latin ‘finis’, meaning ‘end’, the etymology of the Slovene word implies a different understanding of the entity of the border. Meja comes from ‘med’: in between, in the middle. “You can be a citizen or you can be stateless, but it is difficult to imagine being a border” André Green, a French psychoanalyst once remarked. Imagining precisely this – being a border – is the task of cultural initiatives working in the borderlands.

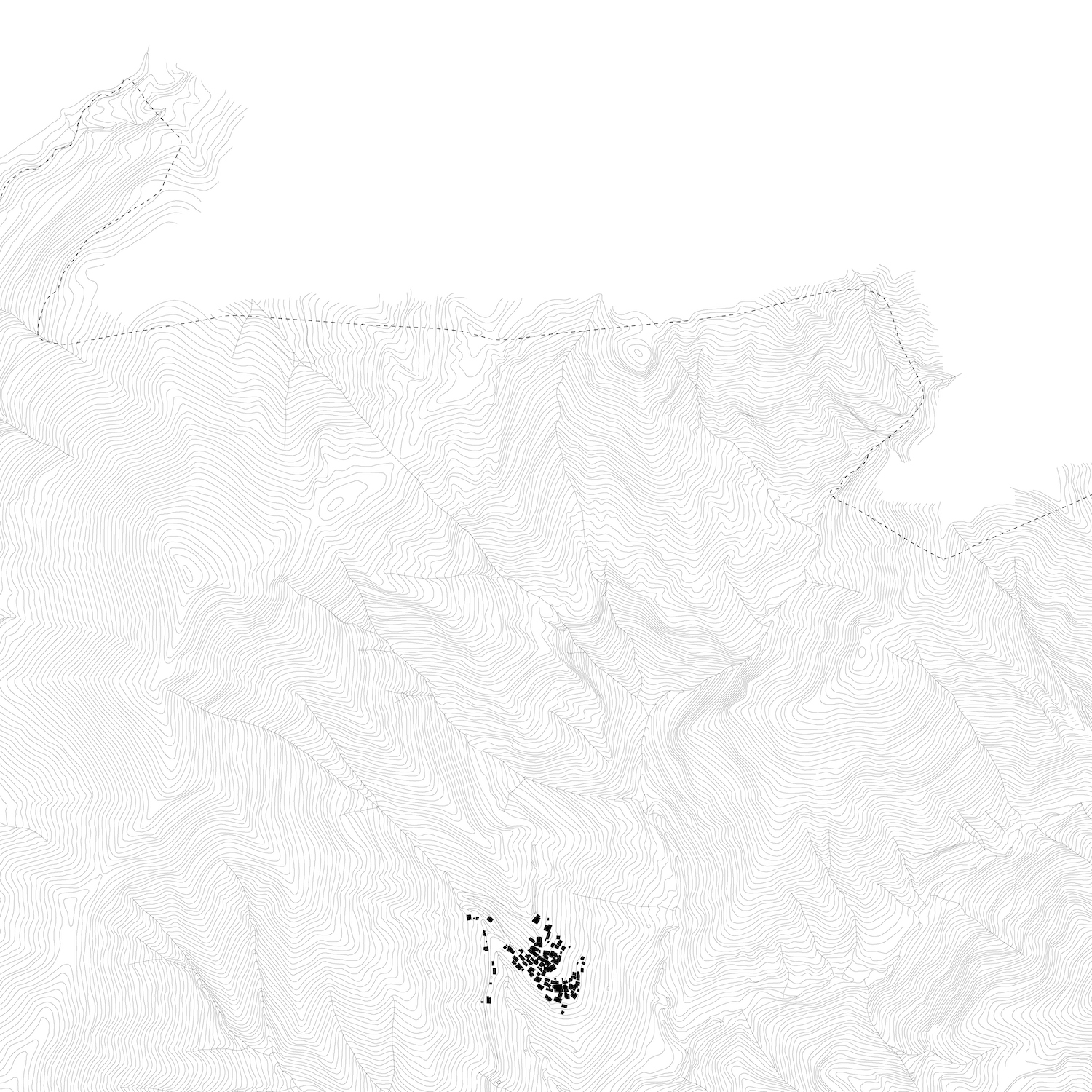

History of the 20th century used the borderland which Topolò/Topolove is part of as the background of some of the most violent WW1 operations, fascism oppressed the Slovene minority of the area and the Cold War completely transformed the territory into a military zone that should be emptied of its inhabitants: this history brought to the almost complete loss of population, loss of language and identity and the destruction of a community.

This specific border is also a meeting place of the Mediterranean and Alpine climates. This ecotone is a site of “a complex interplay of life forces where plant communities, and the creatures they support, intermingle in mosaics or change abruptly” writes Florence Krall in her book Ecotone: Wayfaring on the Margins.

These spaces of unstable identities and more-than-human intermiglings we call the margins: spaces of radical openness and creative productivity, which enable a minoritarian-becoming directed in several directions, a becoming that is so characteristic of the margins as “zones of unpredictability at the edges of discursive stability, where contradictory discourses overlap, or where discrepant kinds of meaning-making converge.” (Anna Tsing, From the Margins)

This is perhaps the charm of being in the margins: to be able to embrace all sides, to create and maintain a space of permanent convening, assembling and interweaving. To be a crossroads.

The places where cultures, natures, life worlds, experiences, and ideas collide and intermingle are ecotones; the places on the margins where mainstream culture is met and challenged by other forms are particularly fertile with possibilities for change.

— Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands, “The Marginal World” in Every Grain of Sand: Canadian Perspectives on Ecology and Environment, 2004

To be in the margin is to be part of the whole but outside the main body. As black Americans living in a small Kentucky town, the railroad tracks were a daily reminder of our marginality. […] Living as we did-on the edge-we developed a particular way of seeing reality. We looked both from the outside in and and from the inside out. We focused our attention on the center as well as on the margin. We understood both. This mode of seeing reminded us of the existence of a whole universe, a main body made up of both margin and center.

— bell hooks, Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, 1984

KOZOLEC (sl. hayrack)

Kozolec or how to turn rurality into a method. The word is translated into English as hayrack but we like to use the original Slovene word since the english translation is quite generic, indicating a structure where to hang to dry hay.

In Topolò/Topolove we have two ‘kozolci’ (pl. of kozolec): they are open buildings, majestic for their dimensions and humble for their materiality. They stand on four or six pillars made of stone and are covered by a roof made of metal sheets and once of straw. The pillars are connected by wooden racks where hay, buckwheat or wheat was dried: these racks were filled up in summer and slowly emptied until winter. The ‘kozolec’ is therefore an architecture showing, in its filled or empty structure, the passage of season, the cyclicity of time. A calendar in the shape of a house or a temple which accompanies our reflections about the cyclical time, or seasonality, of our own practice.

Even if our work as Robida collective is not directly related to agriculture and therefore not intrinsically linked to the change and progression of seasons, by pointing our gazes towards the activities, atmospheres, situations, and happenings that we are building during the year, we understand that living surrounded by a cyclicly transforming nature and under strong influences of the weather in times of climate crisis impacted our contents, methodologies and ways of dwelling.

Times of reflection and digestion, times of action and commonality. Loud hectic months and slow silent months, introverted and extroverted selves – we become ourselves calendars, as well as the activities we carry on, influenced by the changing forest, the humidity in the air, the steady movement of the vegetation and the sun caressing the walls of our houses.

“Weathering also names a practice or a tactic: to weather means to pay attention to how bodies and places respond to weather-worlds which they are also making; to weather responsively means to consider how we might weather differently—better—and act in ways that can move towards such change.”

– Astrida Neimanis & Jennifer Mae Hamilton, Weathering

VAS (sl. village)

The Slovene word 'vas' (eng. village) has a beautiful Indo-European root *ueik'- which means “to enter, come into, settle”. Entering the village means settling into the cracks. It does not mean to occupy its surface, but rather to enter the depths of the village and to embody its stories.

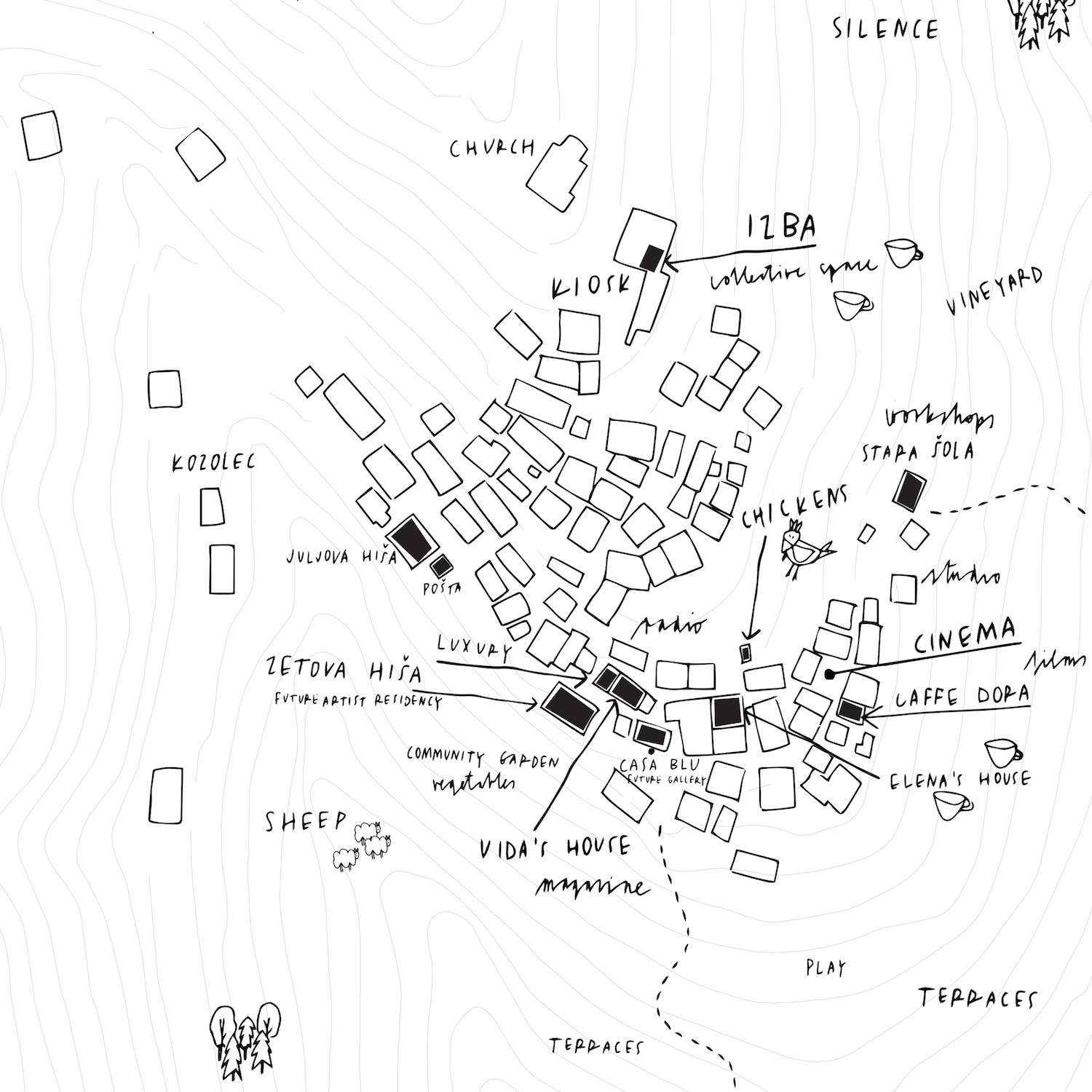

The architectural project Topolò/Topolove – The Village as a House, speaks of this settling in the cracks and inhabiting the village differently. The project started as a master’s thesis by Janja Šušnjar, member of Robida collective, and it is now embraced by the collective as a long-term research, architectural concept and everyday practice. It proposes a new understanding of the village of Topolò, where Robida is based, enabling new content and meaning for existing abandoned buildings and envisioning a different way of dwelling in the place.

The project addresses the wider issue of abandoned, almost empty villages that dot many post-rural territories of Italy: it imagines the restoration of the village – of its abandoned houses, neglected public spaces and ruderal landscape – as if it was a decentralised house where singular buildings are its rooms and the small streets between the houses are the connecting hallways.

Such a spatial concept which is build upon the decentralisation of the house invites an extension of the relation of care, which is directed not only to private spaces but also to common buildings and the spaces between them: the idea and practice stimulates inhabitants to actively engage in the care and well-being of the entire village.

Who can be considered an inhabitant and how can this definition be stretched to include different modalities of dwelling and to recognize different agents that produce, transform and care for the place? How to become that which we want to inhabit? How to balance maintenance and life’s dreams? How to live collectively without forgetting each one’s needs? When and how does a space become domesticated?

POSTAJANJA (sl. becomings)

Robida tries to answer a central question: what were the genealogy and inspirations of the project in the village of Topolò/Topolove?

The answer lies in the word “becomings” translated into Slovene language: postajanja.

All the members of Robida have a deep affection to this village: some of us are from there but others built this relationship during many years attending every July for long parts of their lives the festival happening in the village: Stazione di Topolò/Postaja Topolove. The festival became our school, the place where as teenagers we built our culture, values and relations.

This project was born in 1994 and ran for twenty-nine years: it was imagined as a laboratory for contemporary art, music and literature where artists from all over the world would encounter the village and its inhabitants, listening to them and giving something back. There as kids we encountered poetry and music, we timidly learned how to speak English, we met inspiring people who became our teachers and we started to cultivate that special relation to the village.

Stazione di Topolò showed us very beautifully that it is possible to stay in a small, remote and rural place imagining a life based on contemporary culture and deep knowledge of the place: to be at the end of a road that finished at a dense forest, and yet be in the center of the world. To have hospitality as our biggest value, to live with open doors surrounded by friends, to be rooted in an open yet secluded place, to find inspiration and meaning in living on a borderland.

Therefore even if Robida was born in 2017, it was probably born while we were together growing up with Stazione di Topolò, already developing a radical affinity to the village and imagining our lives there.