Petaled spikes, gentle prickles, soft thorns

Robida in conversation with Robida

This text, which traverses the ten years of Robida's life, was published in Robida 10!

The questions and answers were collectively written by Vida, Elena, Janja, Aljaž, Dora, Laura. The answers by different people are not clearly distinguishable: not everyone answered to everything (the answers by different people correspond to a new paragraph) - maybe some of you can detect by the tone, content and style of writing who gave the different answers or maybe it's not so important. Anyway, have fun reading about gossips, memories, guilty pleasures and some more serious things too!

Do you remember when you thought, “Okay, this will be the name”?

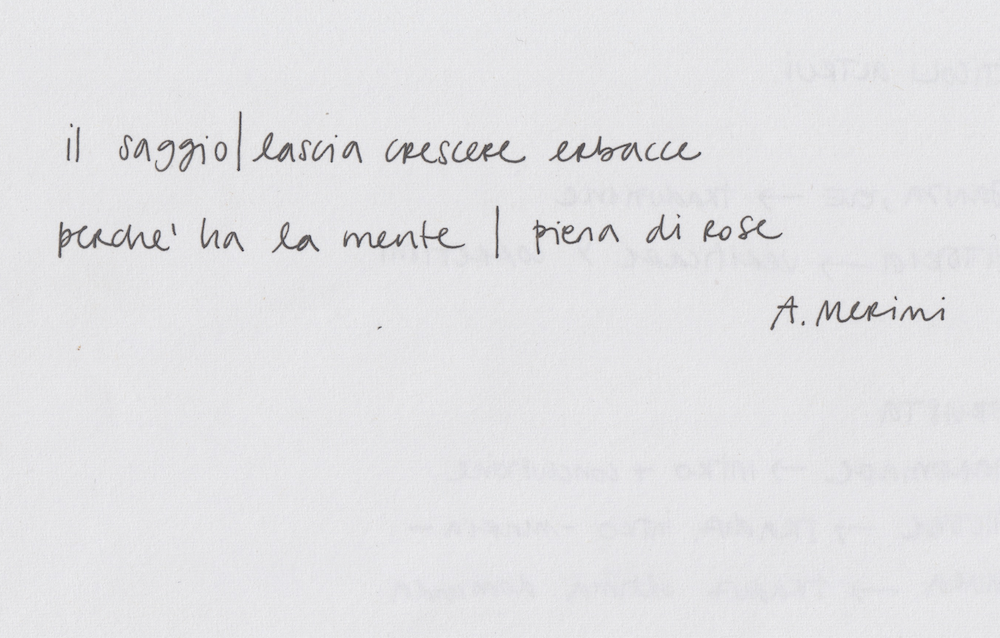

I think I do. Or it’s a story that I repeated in my head so many times that I am convinced it happened. I think it did happen! It was ten years ago. It was July or August and it was extremely warm outside. Maria Moschioni, the co-founder of Robida, and I were sitting on the bed under the window of the kitchen in the house in Topolò/Topolove. And suddenly, reflecting on the epilogue of our previous high school magazine (called La Piperita, which we edited from 2010 to 2012), we realised that it wasn’t actually a closed project, it was just laying there, abandoned, with our new lives at university continuing and the magazine left behind. And so we thought “What’s the first plant that grows on abandoned landscapes?” (The abandoned landscape was of course our previous magazine, that was the metaphor!) That plant is robida, brambles in Slovene, blackberry bushes: that was also the plant that was thriving on the abandoned landscape we were crossing and exploring that summer around Topolò, a plant covering all the abandoned agricultural fields. Then we found this little poem by Alda Merini that says “Il saggio | lascia crescere erbacce | perchè ha la mente piena di rose” (“The wiseman | lets weeds grow | because his mind is full of roses”): in our case – both in the metaphor and in the landscape – our weeds were brambles!

What I like about this name is that it sounds familiar and easy – even if almost no one among our international and Italian friends understands what it means. It sounds so familiar that people of our valley, who are very used to dealing with this plant, call us using the dialect word, instead of the standard Slovene one: they call us arbide and just because this name means something to them, they feel closer to what we do!

If Robida hadn't been born in Topolò, where would you have liked her to be born?

It’s probably clear to everyone that Robida could not have been born anywhere else but in Topolò. But ok, let’s play: it could have been born in Ljubljana, Rome or Venice – which were the cities where many of us were based and met for the first time. And, hmm, if I can choose, I would like her to be born, at the seaside maybe, where it would be nice to meet and develop projects, or in the Netherlands, hah, where we could have received some support and funding instead of working always with almost no money, as we do here! It is nice to imagine it developing in some other rural contexts, in Romagna maybe, in Wales or in Portugal. Or within other minoritarian contexts, in Koroška in Austria, in the Basque countries. Now I think I am listing those places where I would like to develop collaborations with… Which was not the question!

I would wish it had been born in a small seaside village, as far from tourists as Topolò is among its hills, with the same opportunities to breathe new life into places and abandoned homes. And if we want to dream big, I'd love for Robida to have its own little sailboat with its colourful flag!

I was always fascinated by living and staying on a small island. So if I have to really imagine Robida growing somewhere else it would be on a small island in the Mediterranean. It would perhaps have some of the characteristics that Topolò also has: being an isolated place, far away from everything, being a rural place, with traditions that still influence the island itself.

Sometimes when telling the story of Robida I find myself saying: Robida is maybe what Topolò needs, and the way around… but other villages can need and host something else. So, if Robida would be born somewhere else it would be something different, for sure.

Would it have been just as “prickly”?

I truly don’t think so. There is an actual substantial reason why Robida is as it is: being positioned on the border, being a part of an ethnic and linguistic minority, being raised in a place full of strong women. I think that Benečija, the region where Topolò is located, is a place where resistance is inborn.

Do you think Robida still needs its thorns?

Absolutely yes, without its thorns we would be just another romantic plant that gets only appreciation and astonishment. Being a complicated plant, which is quite invasive, difficult to deal with and to live side by side with, is quite interesting! Deciding to call ourselves robida was an invitation (to ourselves first) to look at that plant differently, which does not mean only more gently. And referring to the above question, the thorns remind us to be resistant, even to be political, somehow. We are allowed to be a bit louder or a bit more radical because our reference plant is thorny!

Sure! And maybe sometimes we should be more confident of showing out, of using them. Growing also means becoming wise or in our case prickly.

Try to jump back in time and put yourself in your shoes ten years ago. Is there something that has remained unchanged and something you would like to recover?

Nothing remained unchanged! And the beautiful thing is that Robida (both the magazine and the wider project) changed with us too! Lately, I am reflecting a lot about how Robida is actually a project of our twenties that follows our growth in the time of the biggest changes! How different would it be to start a project like this now? Completely different… We would be more focused, with clearer desires probably, more intention. Robida was (and still is) really an adventure that we went on super lightly and spontaneously, not defining anything at the beginning – what we wanted it to be, what would the guiding values be, what the core topics or main directions were – such lightness and recklessness would be impossible today!

I guess everything changed with us slowly changing, people coming and going, some of them staying. But for me, the core and the meaning haven’t changed: it is still friendship.

I'm pretty sure the only thing that has remained unchanged is that Vida and Elena are still sisters. They are, right?

How did the characteristics of each person find their place within the work group?

A few months ago, we had a very interesting meeting on this topic. Before that moment, we had never addressed the issue. Or better, we had never considered the idea of analysing our strengths and weaknesses and consequently identifying roles that suited us best within the group. For the first time, we all sat around a table and started writing lists and notes about personal characteristics, aspirations, and needs. The most interesting thing was discovering how often the perception we have of ourselves is completely different from how others perceive us, and that the roles we occupy do not necessarily align with what comes easiest to us. Seeing everything so clearly, in black and white, gave us a more conscious understanding of our abilities, which helped us feel more relaxed within the group and better manage complex situations.

A lot of time people ask us about how we are organised, which are our roles depending on our personal character. And it’s very difficult to answer. For sure there are members who are more capable of having new ideas, who are good at weaving relationships, who are good at solving problems, who are good at being consistent and finalising a project. Since we are different, with different passions and qualities, everyone finds their place depending on the type of project (more local or not), the topics, the timing (some of us are working on other things), the place (here in Topolò or somewhere else)... everything is natural and spontaneous.

Hah, sometimes this does not happen so smoothly, to be honest… Very often we don’t all agree with things, because we have very different tastes and methodologies of doing things. But it’s also true that Robida is such a wide project, with many different sub-projects, that all these diverse ways can definitely find their place. Sometimes I would like more coherence in what we do but at other times this multiplicity of languages, tastes, interests, personal tendencies becomes one of the biggest qualities of Robida.

“Fake it until you make it” is a widely successful expression and, like all sayings, it contains an authentic pearl of truth in a rather modest shell. Was there a time when Robida “pretended” to be something it wasn't yet? And when did it finally reach the recognizable form it has today?

I think that for answering this question we need to start by making a very artificial distinction between the Robida Magazine and the other activities Robida does as an association and a collective. Editing and publishing a magazine definitely needs a bit of faking. After all, it is expected of you to truly know the topic you deal with throughout the whole year. Presentations of magazines are also structured in this way: We, editors, are subjects who are supposed to know. And knowing needs faking, I think. On the other hand, other parts of Robida’s activities – organising, convening, bringing people together in informal situations of situated learning – present, at least for me, a very open expression of not-knowing, of wanting to learn and develop, creating new affinities to different particles of life. It is not a sort of an “ignorant schoolmaster” attitude, not at all. I truly don’t know, but would love to know. And I hope others feel this, as I think this sincerity is what makes Robida so valuable.

I somehow always hated this sentence, ahahah! And actually, I think that it does not refer to us at all. Such a guiding sentence probably implies that you at least have a plan or a goal that you are working towards, or faking about and for. And Robida never really had this clear direction for everyone to go towards… Which is both positive – spontaneity, freedom of trying things, playfulness – but also negative – absence of clear goals, fluctuation over things, etc. I think our guiding principle sounds more like “Make it until you make it” which comes with a continuous and steady doing. Doing things just because they seem interesting, they make us happy, they look challenging, they make us meet cool people, etc. So, I think that Robida never pretended; that would be too much of a complex way of reasoning. And Robida was rarely about reasoning, planning, or designing.

I also perceive this saying with a negative connotation – I would like to believe that Robida always enables dreams to become a tangible experience, through fearless trying, supporting the ones that are maybe less brave, acting with a lightness towards the challenges that could in some other environments actually represent quite a complex organisation… And with this attitude – everything is possible, even if you fail the first time – Robida slowly weaves the story that is bigger than the initial idea (whatever it was – I guess we already forgot). Not with trying to prove anything to anyone, but trying to do what you think is good and could be even better.

Robida is for me the place where ideas or dreams are put into practice and find a form outside our mind. So, maybe the idealisation, the initial enthusiasm behind needs a bit of utopian trust in our capacity… but after that it is actually a serious responsibility to transform the idea into something real, to transform conversations in spaces, publications, moments to share and realise that we can actually make it. This is somehow helping me/us to grow and think bigger, with a bit of fantasy but always for real.

What has been one of the funniest situations you have faced over the years?

I remember the time when we all left Topolò to go to Izola in Slovenia, where we were going to set up an exhibition in a completely empty hall. True to Robida's style, we thought it was vital to make it as cute and welcoming as possible. So, we packed our cars to the brim with all kinds of items: rugs, pillows, stools, vases, and of course, plants. We took our plants on a seaside trip! Those were super fun days, it felt like a high school trip but without teachers to supervise us. We had rented a house with a terrace, and of course, many more people stayed there than originally planned...

I think it is always funny when we break a routine – when we go somewhere together, when we do things that are not on the official curriculum (not that it exists) – for example taking care of the food for Senjam – being a waitress with your best friends and taking selfies with a Slovene president – quite a fun moment.

I have the feeling that Robida is not just a “cultural” project, nor just a collective. It seems more like a way of choosing to live, of giving space and value to certain concepts over others... Am I wrong?

It certainly can be a topic of discussion capable of entertaining an unexpected range of interlocutors! In fact, saying that it is a project that, among other things, publishes a magazine once a year, doesn't exactly give the right idea. I would rather describe it as a constant drive to ask many questions. And not just in the editorial or cultural field in general. Being part of a collective project is very different from pursuing one's personal research. It involves dialogue and compromises, and above all, responsibility, which is multiplied by the number of people involved. We often find ourselves questioning why we do it, as financial gain is certainly not the answer. Sometimes I see it as a privilege to be respected and cared for, and, like all privileges, I feel the need to share it. Other times, I like to think of it as a politically radical action: in a world where everything is about work and profit, cultivating something whose fruits don’t reduce to material gain seems to me a revolutionary act. And this inevitably ends up influencing your life even outside the moments when you are actually working on it.

The people that make Robida transformed their lives so much in the last years – shifting from post-university period to work life – that Robida had to change a lot too. When Robida was in its most beautiful and intense time, it really was primarily a way of living together: none of us had jobs for which we would need to move daily and leave Topolò, we all were in this beautiful limbo of life between the end of the studies and having to find jobs, when everything seemed easy, from opening up abandoned fields all covered with robida and cutting the plants by hand, to making a magazine in two months, to opening an almost-caffè in three months. And I think Robida is still transforming while our lives transform. I would say that Robida rather than being a project, which etymologically speaking somehow implies a focus and a direction, it is a practice (a word that Dora is making great fun of!). It’s a practice precisely because it’s something that we just do, continuously, even without questioning it too much or making decisions. It’s a practice because it accompanies our everyday lives and it’s shaped around them, morphing with the changing rhythms of our lives.

I think that what makes us strong is having similar values. Also if we are not all living in Topolò constantly there are some ideals of how to live together, how to spend time, how to grow stuff that is common. Sharing spaces, sharing ideas, working together, being slow (and efficient) in different moments of the year, listening to each other, being open and honest… Sometimes there are some specific topics that put us together, sometimes it’s only a strong friendship!

I think Robida brings culture back to its roots: to cultivate, grow, and nourish something. The etymology of the word and the true essence of culture are so easily forgotten in cultural work. It’s as if philosophy forgot to think, education forgot to teach and so on. With Robida, it all comes down to transforming one’s way of being and living, in times when both are on the brink of collapse. Robida proposes a chaotic inventory of practices that helps doing just that, connecting us to different stuff around us. But then again, isn’t that what culture is all about?

Do you think your readers have a realistic idea of what Robida is and what its internal mechanisms are?

There was a period, perhaps during the planning of the new website, when we often talked about the difference in perception one might have when observing Robida only through social media or publications compared to the impression one gets from knowing us in person or spending a few days in Topolò. We specifically asked our guests to share their impressions once they crossed the barrier of the phone screen.

It’s also true that it's not easy to explain how Robida works in every aspect because, contrary to what it may seem, most of what happens is the result of spontaneous impulses, experiments, and sometimes even bets against time and… space.

Not at all, but I also think it’s quite normal. Sometimes we tend to give the impression that we are extremely professional (also in the sense that this might be perceived as our work, profession!), while we are still perceiving ourselves as a group of friends making things with other friends!

How important has it been to create moments where you can meet in person rather than remotely?

Being able to spend time together is crucial, especially to remind ourselves that it's not always just about work. A project like Robida, whose timing and goals are driven by curiosity and a desire to explore and build relationships, also thrives on what happens in person. Being physically together doesn’t necessarily mean working more or better, but rather creating the conditions for something unexpected to happen. Then there are those even rarer moments when we are together but not working, just relaxing and enjoying each other's company.

What would be important, for sure, is having soft and relaxing moments with each other but also – and we miss this even more, I think – discussing things. Usually, if we are together for Robida’s projects – the magazine, the Academy of Margins’ Summer School or others – we spend time mainly solving concrete questions while we tend to relegate to Google Docs and emails moments of reflection and construction of ideas…

Which were the nicest ideas/reflections/intuitions that sprouted within Robida?

Usually, the nicest reflections and intuitions that I have about, within or around Robida come in the moments when I present Robida or when I write about our projects and practice. The intuition of situated publishing, which the summer school of this year revolved around, or that of soft utopia, which came out while writing a text about Robida for a publication about dreams (Dreams of Dreams of Dreams, published by Onomatopee, 2024) for instance. Then there is the idea of the Academy of Margins, that developed in a sleepless night. Other reflections sprouted from conversations, such as the idea of learning with the landscape, born out of a conversation with Michael Marder…And then there is one of the most interesting ideas, the one of the village as house, that was born as part of Janja’s research on Topolò for her master’s thesis. Many of these small intuitions, reflections and invented concepts are collected in our Glossary of the Margins.

What questions do people ask you most often about Robida?

But...what exactly is Robida?

Who is Robida? (the most difficult question ever, ah, I hate it)

Do you really live there the whole year?

(To Franca): Are you Vida? Are you Elena?

How do you sustain yourselves?

Sometimes it happens that people lead a very pleasant and fulfilling life, but deep down they harbour a secret desire to do something entirely different, perhaps less conventionally acceptable. Let's even say, unfairly, a guilty pleasure. What would Robida be if not what it is? What is its guilty pleasure?

Gossip magazine.

Chips and a bit of fancy beer.

Decorations with flowers and plants.

I think that we all like simple beauty. So we care about it and make everything a bit more beautiful just because we like it.

A beautiful cake.