Trees of Topolò / Topolove

Ever since Vida mentioned during the Academy of Margins, the summer school programme Robida hosted in 2024, that the trees on the mountains surrounding Topolò are fairly recent additions to the landscape, I’ve been thinking about these newcomers.

I am gathering their names in our [1] languages, so far I found:

EN / IT / SL / PT / NL

Summer oak / Quercia peduncolata / Hrast lužnjak / Carvalho pedunculado / Zomereik

Field maple / Acero campestre / Poljski javor / Bordo de campo / Veldesdoorn

Chestnut / Castagna / Kostanj / Castanha / Tamme kastanje [2]

Beech / Faggio / Bukev / Faia / Beuk

Linden / Tiglio / Lipa / Tília / Linde

Elder / Sambuco [3] / Bezeg / Sabugueiro / Vlier [4]

Elm / Olmo / Brest / Olmo / Iep

Curious to engage with these forests surrounding Topolò/Topolove, I wonder: Who and what else dwells here? How do I invite people into the forest using different senses? And how could the forest be recorded through printing and writing practices?

I returned two months after the summer school in the early autumn days of October to find the leaves yellowing, reddening and browning, carried downward by the wind. The Dutch word ‘dwarrelen’ is used for this particular movement, and the way feathers float through the air. There will be many moments during the residency on mornings spent walking where we stop for a moment, and just watch them fall like glitter particles continuously raining between the trees.

There are a few things I had set out to try in these ten days, bringing books; tools like a pocket knife, a linoleum roller and rope; and media like inks and clay. The rest could be borrowed, like Elena’s glass plate and bookbinding thread, Robida’s generous stash of paper, Vida’s printer, Elena and Antônio’s kitchen, Vida’s bread-making skills and flour, and throughout, Antônio’s time [companions/camminiamo]. Within my time in time in Topolò, the experiments I wanted to do involved woodworm-drawings [companions/impronta], building passages in the forest [traversata/passaggio], eating acorns [seminare/ghiande] and collecting these efforts in a small publication. This fragmentary register is a reworking based on the texts from the publication, complemented by additional context, images and the video documentation Antônio made.

COMPANIONS / IMPRONTA

Something which already caught my attention in August in Topolò during the Summer School, were the fallen trees and logs in the forest showing intricate patterns made by woodworms. Their beautiful artworks are revealed for just anybody to see when the wind pushes the trees a little too roughly, or the ground loosens so they trip over their own roots and stumble, toppling over—when lightning strikes, or a piece of bark comes peeling off. Pathways and patterns, the infrastructures of the woodworm’s sustenance, come into view. It is something that has fascinated me for a long time. In 2019 during a residency in Sweden at Bluesberry Woods I took a piece of decorated bark back home. In 2022 I got these worm’s drawings translated to my body as a tattoo, so I would move them along with me.

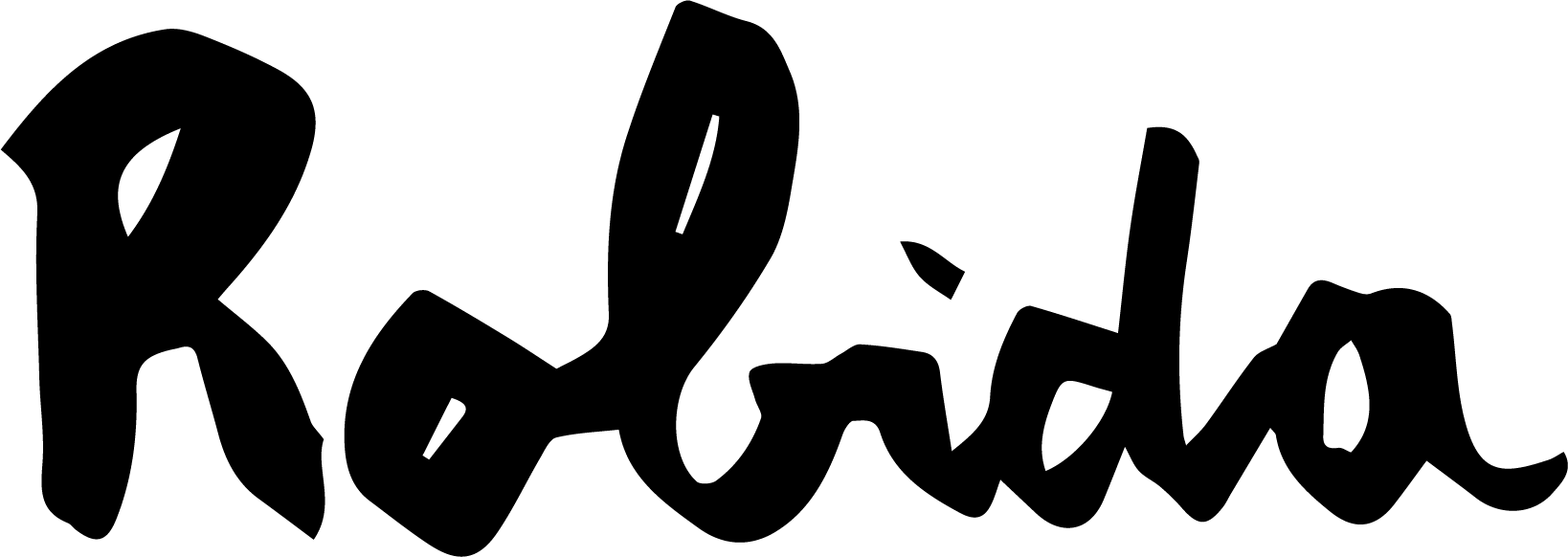

I had been curious to find other ways of recording the woodworms’ drawings and thought to reprint them. Moulding clay pressed into these carvings would function as both an intermediate and create an artefact. The clay forms a negative, creating hills where there are grooves, and rolling ink on these elevations makes opaque lines where once there were engravings. These squiggly, subtle differences that decorate the forest throughout absolutely captivate my attention—I wanted to try translating these traces.

COMPANIONS / CAMMINIAMO

More often than not, me and Antônio start the day with a walk. What if we followed the river upwards?—There is another cave?—Let’s cross the border!—Today we find fallen trees to make stamps, when all is done we’ll swim! During our walks we embrace the rain that soaks our socks; spot many sprouting mushrooms; and are greeted by clouds whirling between the trees [5] on our ways.

When the colours of the leaves change even throughout my mere ten days of visiting Topolò, I imagine how the same walk would change every week. My mother tells me that is why she walks the same route every Sunday, to behold these transformations and to find joy in the passage of time. Another way my experience of time is marked during the residency, is by the ways my days feel divided into parts and rhythms. They are often decided by being outdoors, indoors, eating (or not yet), reading (or not yet), by being together and alone. I wonder what keeps the orchestra in tune, and how Topolò functions as a stage–a shared plane/place that invites these rhythmic interactions. Perhaps the steps it takes—to get from one house to the other, from where I sleep to the warmth of Elena and Antônio’s house, to Vida and Aljaž’s kitchen or terrace, up to IZBA, past Dora’s house down to the river, or even further up towards the antenna—function as intermezzos playing between our interactions, interludes between these different parts of my days. Not necessarily motivated by reason or desire [6], this walking is a kind of composing of time and place. I like the sound of that.

Then, going with ten of us into the forest on the Friday I presented my work, feels like leading an ensemble. Queue the conductor’s nerves.

TRAVERSATA / PASSAGGIO

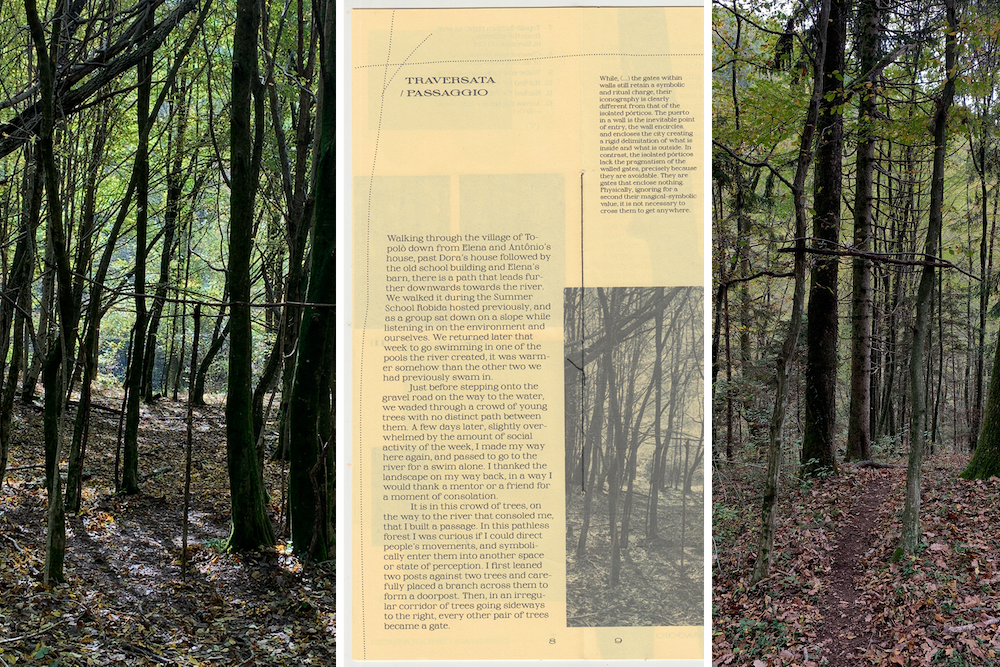

Through the village of Topolò down from Elena and Antônio’s house, past Dora’s house followed by the old school building and Elena’s barn, there is a path that leads further downwards towards the river. We walked it during the Summer School, being invited by Johanna (Gratzer) as a group to sit down on a slope while listening in on the environment and ourselves. We returned later that week to go swimming in another one of the pools the river created.

Just before stepping onto the gravel road on the way to the water, we waded through a crowd of young trees with no distinct path between them. A few days later, slightly overwhelmed by the amount of social activity of the week, I made my way here again, and passed to go to the river for a swim alone. I thanked the landscape on my way back, in a way I would thank a mentor or a friend for a moment of consolation.

It is in this crowd of trees, on the way to the river that consoled me, that I built a passage. In this pathless forest I was curious if I could direct people’s movements, and symbolically enter them into another space or state of perception. I first leaned two posts against two trees and carefully placed a branch across them to form a doorpost. Then, in an irregular corridor of trees going sideways to the right, every other pair of trees became a gate.

A while ago while discussing the books of Ursula Le Guin with a friend, he told me about the thesis project for which he had collected visual archival material of thresholds, and discussions of such passage ways in anthropological and ethnographic texts. During this experiment I wanted to do in Topolò I asked if I could read the thesis, but it was entirely in Spanish. I did my best to translate it to English and, with Ismael’s revisions, share his argument about the way an unenclosed gate charges a landscape with meaning differently than a doorway of a building might. Ismael writes that:

“While, (...) walled gateways still retain a symbolic and ritual charge, their iconography is clearly different from that of isolated pórticos. The gate in a wall is the inevitable point of entry, the wall encircles and encloses the city creating a rigid delimitation of what is inside and what is outside. In contrast, the isolated pórticos lack the pragmatism of walled gates, precisely because they are avoidable. They are gates that enclose nothing. Physically, ignoring for a second their magical-symbolic value, it is not necessary to cross them to get anywhere. I think it is reasonable to say that it is precisely this practical uselessness that charges them with meaning. Crossing an untethered door is not necessary to physically get anywhere. Therefore, to some extent, going through it is an optional act. If going through the door does not physically lead anywhere, then it must do so symbolically or spiritually. The door must lead somewhere.” [7]

I continued to think about how to enter and exit the gates I built and what this would somehow entail. Raking the leaves on the inside of all these portals, differentiating the space inside and outside, felt completely wrong. The strong urge to change it was almost comical. Like Ismael writes, these gates should enclose nothing, but nonetheless invoke the suggestion of leading somewhere. This was not to be a dwelling but a passage, much like the way the doorposts are not a permanent fixture to this landscape but a gesture with/in it. Much like also my staying in Topolò/Topolove in residency, is a temporary dwelling. A conversation with a place.

Coming back after another day, some leaves had fallen again in the places me and Antônio had removed them. I started instead to trace paths between the doorposts, dragging my feet over the forest floor. An entrance here, an exit there, a branching path into another direction. Every path connected, like a loop or circuit, inviting one in and out of the portals. The result was a focused experience, carefully placing one’s steps to weave through the trunks and branches. Alone it transformed from a disorienting experience into a meditative one, but I wondered if together it would turn into something else.

I became curious to know what would happen if people were to cross in this space. When I invited others in, how would they negotiate this meeting?

Walking on the paths through the portals with two people became much more like a game, your choices of direction both guided by the paths, and chosen based also on the awareness of another’s presence. A conversation with a place, becoming also a collaboration with another person.

Then, one solitary gate, a few hundred metres before the cluster of trees and portals, marks another possible entrance or exit. It is easy to miss in the landscape, but consider finding and entering it the first invitation, and a possibility for return to the topside world. Although, this I cannot guarantee.

SEMINARE / GHIANDE

I wanted to know if I could make something edible with acorns, a nut abundant in the Netherlands that goes unused. Ironically the very readily edible sweet chestnuts were abundant in Italy, which I hadn’t realised beforehand. They are more rare in The Netherlands, where local species did not survive past the latest ice age. During my stay in Topolò I might have eaten more chestnuts than I had before in my entire life. Nonetheless I also introduced everyone to the taste of acorns, transformed into bread and coffee as the result of the following experiment.

16 October

Picking acorns, one jacket pocket full. I lay them out to dry on a brown handkerchief.

18 October

Together with Antônio and Elena I peel the acorns, some we smash with a stone on its end, some we cut in half.

People who come by and see the acorns are surprised they can be eaten. I tell them it is my first time trying to make them into food.

19 October

In the morning I notice the peeled acorns have browned. We cut away the browning parts and put them in cold water.

We go out to pick up some more acorns, and I begin peeling again. In the evening I put a pan on the heated stove to boil the peeled acorns in.

20 October

In the morning I rinse the boiled acorns and taste one, it is not bitter, but it is a dull dusty taste.

I cut them into smaller pieces and we put these on a baking tray to dry out in the sun.

21 October

It is another sunny day, but the acorns have not completely dried. In the afternoon I put them in the warmed (70 C) part at the bottom of the stove.

22 October

In the afternoon, before the stove is heated fully, I take out the tray from the bottom. They have browned some more and seem dry enough to use for flour [8] or coffee [9].

24 October

After lunch, Vida helps me grind the acorns to flour and we are able to use 30 grams to mix with spelt and plain flour to make sourdough bread.

Thank you

Dear Robida, thank you for hosting me and for the chance to see another season of Topolo’s / Topolove’s forests. It was with great pleasure that I got to experiment with techniques and ideas that I held close for a long time!

Until we meet again,

Heike

[1] Vida, Elena, Dora, Aljaž who speak Italian, Slovene and English, Antônio who speaks Italian, Brazilian Portuguese and English, and I speak Dutch and English.

[2] Dutch calls the inedible horse chestnut colloquially "chestnut tree" and adds "tame" to the, in the Dutch landscape, more rare edible chestnut variation. In actuality the trees are not at all related kinds, their nuts just look similar.

[3] Literally means “elder”, but is derived from “sambux”, a red dye.

[4] The Dutch name is derived from the fluttering of the leaves.

[5] There is a Dutch folktale about sweeping banks of mist in swamps and forests called the “witte wieven” and I am in awe to see so many.

[6] But sometimes also by structures themselves, like how Robida describes in the project The Village as a House, that the village’s paths become hallways where some of the houses in Topolò require one to go outside to access different rooms.

[7] Ismael Abderrahim Arribas, “Sobre Puertas Y Umbrales. Un Diseño Editorial Entre Imágenes Y Textos” (MA Thesis, Universidad Complutense Madrid, 2023), p. 23. Translated to English by Heike Renée de Wit, 2024.

Original in Spanish: “A pesar de que, como ya he dicho, las puertas de la muralla aún conservan una carga simbólica y ritual, su iconografía es claramente distinta a la de los pórticos aislados. La puerta de la muralla es el punto de entrada inevitable, la muralla circunda y cerca la ciudad creando una delimitación rígida sobre qué está dentro y qué queda fuera. En contraste los pórticos aislados carecen del pragmatismo de las puertas de la muralla precisamente porque son evitables. Son puertas que no cercan nada. Físicamente, ignorando por un segundo su valor mágico-simbólico, no es necesario cruzarlas para llegar a ninguna parte. Creo que es coherente pensar que es precisamente esta inutilidad práctica la que las carga de significado. Atravesar una puerta exenta no es necesario para llegar físicamente a ninguna parte. Por tanto, hasta cierto punto, atravesarla es un acto opcional. Si atravesar la puerta no conduce físicamente a ninguna parte, entonces debe hacerlo simbólica o espiritualmente. La puerta debe llevar a algún sitio.”

[8] To make flour you put the finely cut pieces of dried acorn in a coffee grinder or food processor and grind it to a fine powder.

[9] To make coffee you grind the acorn pieces into a coarse grain, roast a palmful until fragrant and mix it with boiling water and a few teaspoons of coffee in a pot on the stove. Boil the coffee for 10 minutes and strain.

Here you can listen to the conversation between Heike and Vida on Heike's residency experience in Topolò!

Heike's residency is part of the project Sensing Soils, supported by Regione Friuli-Venezia Giulia.